Elizabeth Goodman. May-June 2014. Design and ethics in the era of big data. interactions 21, 3 (May 2014), 22-24.

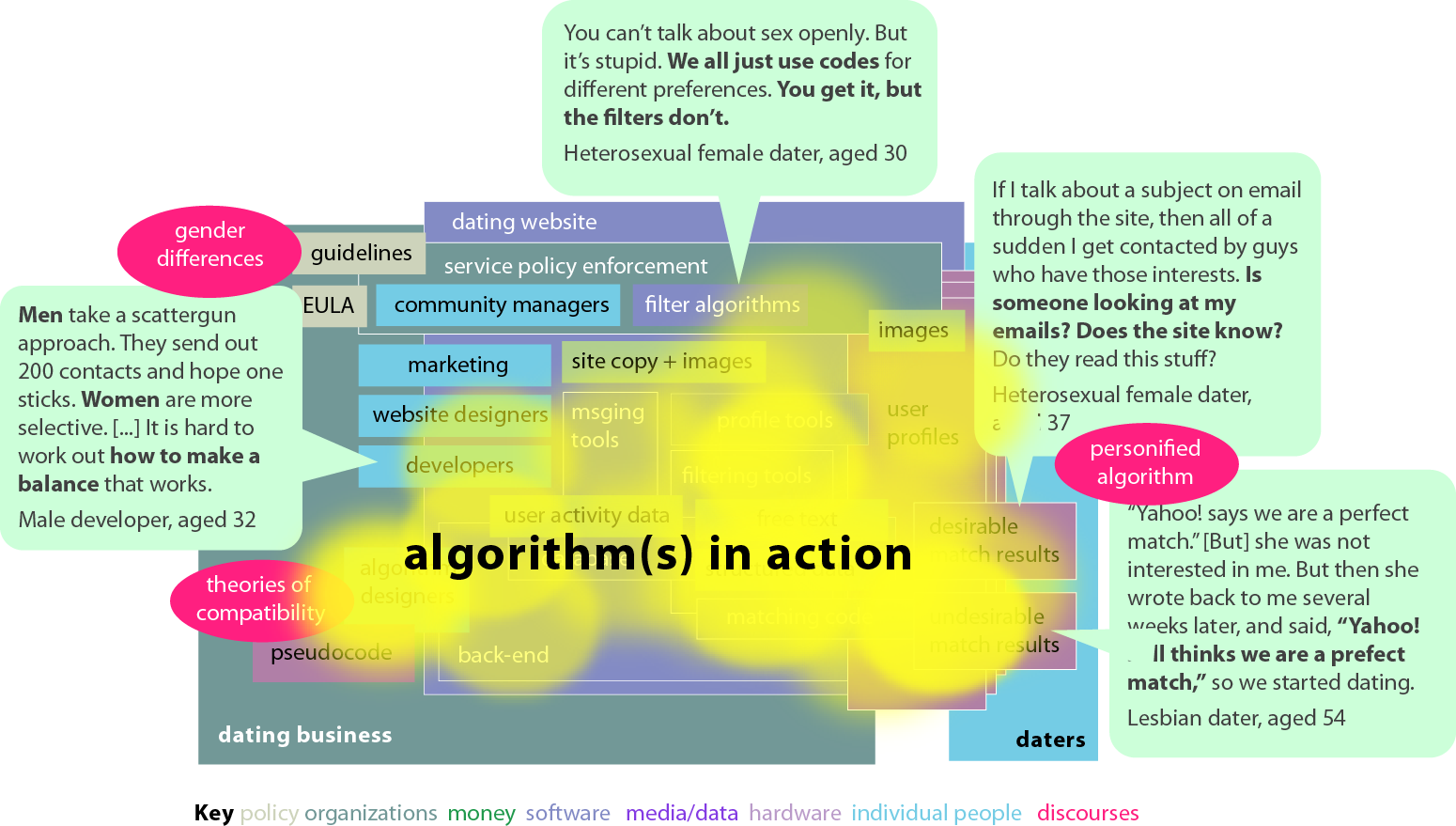

May 15 | The Algorithm Multiple, The Algorithm Material: Reconstructing Creative Practice | UC Davis

Traditionally, computer scientists define an algorithm as a list of instructions for accomplishing a single goal. This definition treats an algorithm as (1) a coherent, usually textual, single object that (2) can be separated from its technological execution. Instead, we argue for the usefulness of studying algorithms in and as action. Algorithms-in-action, particularly computational algorithms, depend on actors outside them: the sources of the data they require as inputs, the machines that execute them, the storehouses that maintain their results and make them available for other processes, and so on. Algorithms are not stable texts but rather more-or-less stable agglomerations of people, machines, policies, data, and so on whose dimensions and components change over time. Our talk will examine the multiplicity and contingency of algorithms through two case studies from very different algorithmic sites — architectural software, and online dating services. Using those sites as springboards, it will argue that taking algorithms as multiple rather than singular and as material agglomerations rather than discursive texts opens up new entry points for creative and critical practice in design, the arts, and engineering.

The Decay of Digital Things

With Andrew Lovett-Barron and Maryanna Rogers, I taught a pop-up studio workshop called “The Decay of Digital Things” at Stanford’s d.school this May. Using examples from iPhone operating systems to aged and eccentric artificial intelligences, we made speculative prototypes exploring future deaths and afterlifes for computational objects.

Delivering Design: Performance and Materiality in Professional Interaction Design

Interaction design is the definition of digital behavior, from desktop software and mobile applications to components of appliances, automobiles, and even biomedical devices. Where architects plan buildings, graphic designers make visual compositions, and industrial designers give form to three-dimensional objects, interaction designers define the digital components of products and services. These include websites, mobile applications, desktop software, automobiles, consumer electronics, and more. Interaction design is a relatively new but fast-growing discipline, emerging with the explosive growth of the World Wide Web. In a software-saturated world, every day, multiple times a day, billions of people encounter the work products of interaction design.

Given the reach of their profession, how interaction designers work is of paramount concern. In considering interaction design, this dissertation turns away from a longstanding question of design studies: How does interaction design demonstrate a special form of human thought? And towards a set of questions drawn from practice-oriented studies of science and technology: What kinds of objects and subjects do interaction design practices make, and how do those practices produce them?

Based on participant observation at three San Francisco interaction design consultancies and interviews with designers in California’s Bay Area, this dissertation argues that performance practices organize interaction design work. By “performance practices,” I mean episodes of storytelling and narrative that take place before an audience of witnesses. These performances instantiate — make visible and tangibly felt — the human and machine behaviors that the static deliverables seem unable on their own to materialize. In doing so, performances of the project help produce and sustain alignment within teams and among designers, clients, and developers.

In this way, a focus on episodes of performance turns our concerns from cognition, in which artifacts assist design thinking, to one of enactment, in which documents, spaces, tools, and bodies actively participating in producing the identities, responsibilities, and capacities of project constituents. It turns our attention to questions of political representation, materiality and politics. From this perspective, it is not necessarily how designers think but how they stage and orchestrate performances of the project that makes accountable, authoritative decision-making on behalf of clients and prospective users possible.

Design For X?: Distribution Choices and Ethical Design

Goodman, E. and Vertesi, J. 2012. Design For X?: Distribution Choices and Ethical Design. In Proc. CHI EA ’12: 81–90.

Continue reading “Design For X?: Distribution Choices and Ethical Design”

Handwaving and the real work of design

Goodman, E. 2011. Handwaving and the Real Work of Design. interactions, 18(4): 40 – 44.